By: Jamie Stolz, CFP®, MBA

Imagine you suddenly come into a lot of money, like an inheritance, a bonus, or selling a business. Now, you have a choice: Do you put all that money into investments at once, or do you invest it bit by bit over time? This is the debate between two strategies: Dollar Cost Averaging (DCA) and Lump Sum Investing. Let’s break down the pros and cons of each to help you decide how to invest your money.

For some additional insights, check out this video by Ben Felix, a recent guest on The Money & Meaning Show, Dollar Cost Averaging vs. Lump Sum Investing.

| Dollar Cost Averaging | Lump Sum Investing | |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Dollar Cost Averaging means investing equal parts of your lump sum at regular intervals. This approach is often used to ease into the market in an attempt to avoid the regret of investing everything just before a market crash. | Lump sum investing means putting your entire cash lump sum into investments all at once. This approach can offer certain advantages over DCA. |

| Example | For example, if you have $100,000 to invest, you could split it into ten $10,000 portions and invest them over time. | In our example, you’d invest the full $100,000 in a single day. |

| Potential Pros | • Helps you avoid emotional decisions influenced by market fear.

• Reduces the risk of investing a large sum right before a market downturn. |

• Historically, it has often led to better long-term returns compared to DCA.

• It can be more cost-efficient since you avoid recurring trading fees. • It’s simpler with fewer transactions and potentially lower costs. |

| Potential Cons | • Historically, it tends to result in lower returns compared to lump sum investing.

• May have higher costs due to trading fees over time. |

• Emotionally challenging, especially during volatile market times. |

DCA vs. Lump Sum—What the Numbers Say:

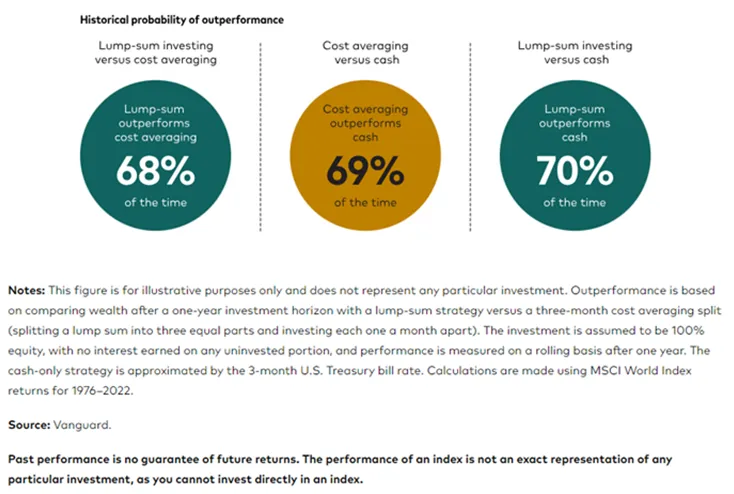

In a recent study by Vanguard, using MSCI World Index returns for 1976–2022, Finlay and Zorn calculated that lump-sum investing outperformed dollar-cost averaging 68% of the time across global markets measured after one year. However, CA was still better than remaining completely in cash; it outperformed cash 69% of the time. According to Megan Finlay, an investment strategist at Vanguard, “highlighting how a cash allocation reflects the opportunity cost of lost risk premium.”

Of course, not all investors aim only to maximize their wealth and would prefer a slower path to portfolio growth if it helps to minimize big drawdowns. Prospect Theory or “loss-aversion” theory, as defined by Investopedia, is the idea that investors place more weight on perceived gains than perceived losses. If two choices are put before an individual, both equal, with one presented in terms of potential gains and the other in terms of possible losses, the former option will be chosen. Although there is no difference in the actual gains or losses of a certain product, the prospect theory says investors will choose the product that offers the most perceived gains.

Psychologists Tversky and Kahneman proposed that losses cause a greater emotional impact on an individual than does an equivalent amount of gain, so given choices presented two ways—with both offering the same result—an individual will pick the option offering perceived gains. To overcome these biases, investors should give extra consideration to choices and reframing possible outcomes. Instead of in terms of gain or loss, you could instead think of it in terms of the value of expected outcomes.

Making an Informed Decision

So, what should you do? Ultimately, the choice between dollar cost averaging and lump sum investing should consider your unique financial situation, risk tolerance, and investment goals. While DCA may provide psychological comfort, it is essential to understand that it may come at the cost of potentially lower returns in the long term.

If you have a lump sum to invest, it is generally advisable to invest it in a risk-appropriate portfolio as soon as possible. However, if the fear of regret is driving you towards DCA, it might be worth reconsidering your asset allocation and finding a balance that suits both your risk tolerance and investment objectives.